The Weaponization of Language (1)

Part 3 of the indoctrination series

John Adams Whipple, Hypnotism, ca. 1845, daguerreotype, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Who controls the language, commands the conscience

Author’s Note

This subject cannot be reduced to a few paragraphs. The dynamics of linguistic weaponization are complex, touching psychology, culture and power. For that reason, I have divided the analysis into two parts. This article focuses on the mechanism itself: how language is stripped of meaning, reloaded with moral weight and used to control thought, along with its effects on individuals and groups. The second part will examine what happens when this process is absorbed by institutions and governments and how it reshapes the moral and political landscape of the West.

The examples discussed here are drawn from progressive movements. That choice does not imply that language weaponization is unique to the left. It can and does occur across the political spectrum. The present cases are simply those that, in my view, most clearly illustrate the scale of polarization now fragmenting Western society.

The Hammer Which Forges Reality

In the previous article, we explored how indoctrination hardens into demoralization. I defined a demoralized person as someone who has internalized a prescribed narrative so deeply that it has become part of their identity, shutting down critical thought altogether and turning every challenge to that narrative into a personal attack.

I discussed why the demoralized mind no longer engages in dialogue but instead labels and ultimately condones violence against anyone or anything that conflicts with its beliefs. I also explained why demoralization always tilts to the extremes of fight or flight. What I did not address is how demoralization spreads once it takes root in a society. This article, and the one that follows, will trace how that contagion spreads.

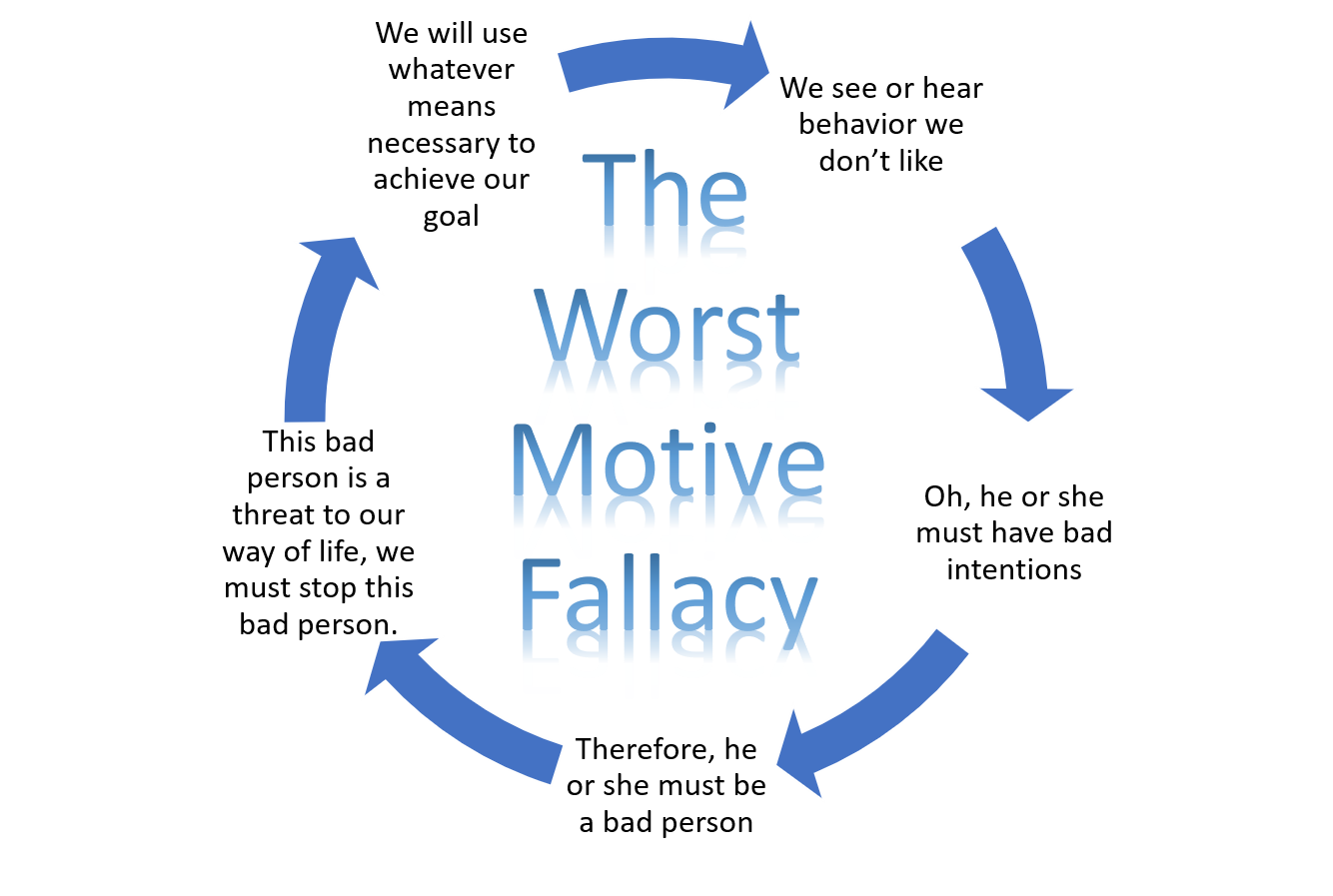

At the core of both indoctrination and demoralization lies a moral filter that predetermines intent. This is the Worst Motive Fallacy: the tendency to assume the worst possible motives behind any behavior we dislike. If someone challenges the approved narrative, they are not mistaken; they are malicious. And of course, the end justifies the means when fighting evil and violence, whether verbal or physical, becomes acceptable to those who take pride in their own virtue.

I will trace this fallacy throughout the article, as it operates beneath every layer of language control. For a deeper look at this psychological mechanism, I wrote a separate piece last year, which you can find here: The Worst Motive Fallacy.

From my own experience, speaking up against attacks on Jewish people in Western countries is almost always interpreted by Gaza-support groups as proof that I am a Zionist and an uncritical supporter of Israel. I have been called a “Zionist liar” and held personally responsible for the deaths of non-Jews worldwide. All for refusing the idea that a religious conflict in the Middle East could ever justify violence against civilians in Amsterdam, Manchester or New York.

This reflex illustrates what happens when language no longer describes reality but enforces moral allegiance. Once language control redraws the boundaries of free speech, debate becomes impossible. Words are stripped of their original meaning, labels are weaponized and entire categories of thought are declared off-limits. As a result, language stops being a bridge between people and becomes a border. Those who use the “right” words are granted moral citizenship; those who do not are cast out as threats. The moral map of society is redrawn. Not by law or reason, but by vocabulary.

The Machinery of Meaning

Words do not become weapons overnight. Beneath the surface lies a psychological mechanism: a three-stage process that strips words of their original meaning, reloads them with inverted morality and spreads the new definitions across society. Language is thereby transformed from a tool of shared understanding into an instrument of social control. Each stage enables the next, ensuring that dissent is disqualified before it is even heard.

The first stage is semantic unmooring: words are detached from their empirical, historical, and moral anchors. “Racism,” for example, no longer requires discriminatory action or intent. A single remark or even a vague feeling of discomfort is enough to label someone racist, regardless of context or factual accuracy. Similarly, “fascism” is no longer used to describe a historical system rooted in state terror and ultranationalism, but to denounce anyone who questions the prevailing moral order.

Once words lose their connection to evidence and history, they no longer point outward to reality but inward to emotion. Meaning becomes reactive rather than descriptive. The listener no longer asks, “Is it true?” but “How does it make me feel?” In that shift, language stops measuring what is true and starts measuring what feels right.

The second stage is moral inversion. Once meaning is severed from reality, words become empty vessels ready to be filled with whatever serves the narrative. And because they retain their familiar sound, they pass unnoticed. No one objects to “safety” or “inclusion” when “safety” means keeping you from harm and “inclusion” means that your different opinion is regarded with the same candor. But when “safety” means silencing dissent and “inclusion” means punishing deviation, words are reframed to mask control as care.

This fusion of language and morality is the most insidious phase of the process. The word “good” is no longer a moral description but becomes an ideological position. Violence, censorship and public humiliation can then be justified, not in spite of morality but in its name. The inversion is complete when coercion is explained as compassion or when violence is justified in the name of peace.

The third stage is language as a gatekeeper of social belonging. Once words have been reassigned their new moral weight, they become a code of access. Speaking the approved terms signals virtue; using the old meanings marks you as untrustworthy. People begin to police each other’s words as proof of allegiance. Old statements are audited and any hesitation to fully agree is interpreted as potential dissent. The community no longer relies on shared values but on shared phrasing.

Ultimately, language no longer describes reality. Instead, it draws a boundary that keeps the righteous in and the dissidents out. On different sides of this border, people can no longer connect through language, because the same sentence now carries incompatible moral weight. And when dialogue is no longer possible, it is replaced with moral diagnoses.

These distortions in meaning do not remain confined to words. Once language itself is reshaped, it begins to reshape the mind that uses it.

How Language Control Constrains the Demoralized Mind

Humans are not rational beings who think in numbers or logic; they think in language.

Language, spoken or non-verbal, provides the framework through which perception is organized, representation is formed and judgment is expressed. It shapes how reality is filtered long before reason begins its work.

In that context, words are not neutral vessels carrying well-defined meanings untouched from mind to mind. They are shaped by interpretation, moral filtering and group dynamics. Through this process, language becomes the architecture of thought itself, determining not only what can be said but what is perceived.

When the meaning of foundational words is systematically detached from empirical reference, the cognitive architecture of language begins to warp. It does not merely change how we communicate with each other; it alters our capacity for independent thought. As a result, our minds are not only misled but lose the ability to recognize that they are being misled.

Language control is a powerful tool to push an indoctrinated mind into a demoralized one. By redefining meaning, alternative theories and perspectives become trapped in language shaped more by morality than by fact. In such a state, the act of offering an alternative interpretation or a different opinion is no longer received as an invitation to dialogue but experienced as an intrusion into morally ordered thought.

This is the logical endpoint of a process in which language no longer describes reality but enforces a prescribed narrative. The demoralized mind does not evaluate the content of an alternative perspective but labels the speaker a threat. The response is exclusion. Labels such as “spreading disinformation,” “feeding extremism,” or “undermining democracy” are invoked as ritual incantations to reaffirm the boundary between the righteous and the dangerous, thereby restoring the illusion that the moral universe remains intact.

As language narrows, perception contracts with it. Words cease to describe the world and begin to dictate which parts of it may be seen. Emotion becomes the filter of thought, admitting only what affirms the moral story already believed. The fewer perspectives one entertains, the more secure one feels in one’s righteousness. Certainty replaces curiosity and the mind mistakes its confinement for clarity.

What begins as an inward distortion soon extends outward. When the same inversion is shared by many, polarization becomes the only possible outcome.

Divided by Design

Once language reshapes thought, its logic inevitably extends outward. It becomes a gatekeeper, no longer describing the world as it is but sorting the people within it. In-groups and out-groups form around a shared allegiance to a redefined vocabulary. At the core of this groupthink lies a rigid victim–perpetrator binary in which every action is read through the lens of identity. If you belong to the oppressed, your behavior is resistance by definition. If you belong to the oppressor, every syllable you utter is taken as proof of complicity. Context vanishes, nuance fades and individual agency dissolves into group identity. And because this language assumes its own righteousness, anyone who dares to criticize is automatically labeled a threat.

How this groupthink operates becomes clear in the next three examples, where the redefinition of words not only deepens division but conceals coercion beneath the language of equality, peace and justice.

The Race-Based Thinking of Antiracism

Antiracism is not a 21st-century invention. The term was already used in the 1950s, when civil-rights leaders promoted race-neutral laws and equal treatment under the law, regardless of skin color. At the time, the Jim Crow laws still enforced daily discrimination against Black Americans. Only with the Civil Rights Act of 1964 were all race-based statutes abolished and discrimination on racial grounds formally prohibited.

For decades, racism was understood as discriminatory behavior rooted in personal prejudice and identifiable in actions or policies. That view began to shift in the 2010s. Under the influence of Critical Race Theory, until then a fringe ideological framework that recasts inequality as the result of institutionalized racism, activists such as Ibram X. Kendi repackaged its core ideas for a mass audience. Racism was redefined as any policy or practice that produces unequal outcomes between groups, regardless of intent or design. Under this new definition, racism became systemic by default, since every unequal outcome is taken as proof of oppression.

As a result, antiracism no longer means opposition to racial discrimination but the pursuit of race-conscious policy: hiring quotas that exclude white candidates regardless of merit, university admissions that downgrade academic performance in favor of ancestry and corporate training that assigns moral status by birth. Identity has replaced responsibility as the measure of virtue. A white person is racist by default unless they endorse race-based policy; a person of color is exempt from criticism because their actions are framed as resistance.

In a short time, antiracism has become the ideological mirror image of the Jim Crow order while producing the same logic. It divides society by race and assigns rights, opportunities and moral worth accordingly. The only difference lies in the moral justification.

Within this framework, “white privilege” functions less as a historical observation than as an inherited sin, passed down like property through generations. The result is entrenchment. By making race the single lens through which equality is seen, contemporary antiracism deepens the very divide it claims to heal. It anchors society in the past, demanding endless penance for sins no living person committed. And because this redefinition presents itself as the only moral stance, dissent is recast as proof of racism and white supremacy, regardless of context or intent.

The same inversion appears in the language of tolerance.

Why the “Religion of Peace” Is Not About Islam

After 1945, Western Europe rebuilt its ruins and redefined its conscience. The Holocaust and the collapse of colonialism shattered the belief in Western moral superiority. From guilt grew new principles: protection became virtue and demanding accountability was branded imperialism. This moral reversal was formalized in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) and the Refugee Convention (1951), alongside broader political and cultural efforts to never again abuse power or deny protection to the vulnerable.

In this atmosphere, Western governments brought in workers from Turkey, Morocco, Algeria and Pakistan to rebuild their economies. When the oil crisis of 1973 halted recruitment, hundreds of thousands were left without work yet were nevertheless invited to stay. Family reunification soon followed and what began as a temporary labor scheme quietly morphed into a permanent presence. Moral conviction outweighed economic sense, laying the groundwork for the mass immigration Western Europe still grapples with today. From the outset, integration was seen as coercion and rejected in favor of cultural preservation. As a result, large Muslim communities, now numbering some 45 million, still grow up largely in cultural isolation, sustained by a Western belief that non-interference is the highest form of virtue.

In the United States, a similar moral reorientation took shape through a different history. The legacy of slavery, segregation and Vietnam had produced a doctrine of white guilt expressed through antiracism and anti-imperialism. Power became synonymous with moral corruption and the center of gravity shifted from principle to identity. Universities and media translated this policy shift into hierarchies of privilege and oppression. Although Islam itself had little presence in America, it was nevertheless adopted under the banner of anti-colonial solidarity and recast as resistance to white imperialism. At the turn of the century, guilt over the past had become the currency of the future on both sides of the Atlantic.

The attacks of September 11, 2001, transformed this shared moral reflex into official doctrine. Only days after the attack, President George W. Bush declared Islam “the religion of peace.” The phrase had nothing to do with theology; it was a political statement meant to calm domestic tensions, prevent reprisals and preserve national unity. Yet Western leaders rushed to endorse the line and within weeks a new moral doctrine was born. In Europe, it spread through NGOs, education and media; in the United States it merged with the language of race and identity. But the gesture of reassurance almost immediately hardened into a kind of moral zeal: to question the phrase was to risk moral condemnation. Protection shifted from Muslims as a people to Islam as a faith, silencing any attempt to analyze Islamist ideology and/ or its link to violence. As such, criticism of both immigration and Islamist intolerance became a moral offense overnight.

Once “the religion of peace” became official truth, European institutions adapted accordingly. The goal was no longer to understand or to solve, but to remain morally untarnished. Police, courts, and social services quickly internalized this creed. In Britain, grooming gangs that abused thousands of girls were ignored for years because officials preferred the comfort of innocence to the risk of being called racist. In Germany, the mass assaults in Cologne on New Year’s Eve 2015 were first reported as “public disorder” until witnesses forced the truth into daylight. In Sweden, public crime reports stopped listing offenders’ origins after 2005 to avoid “stigmatization.” When causes are buried under compassion, policy turns into therapy rather than governance. Across Europe, sexual and ideological violence by Muslim perpetrators was downplayed or stripped of ethnic reference to avoid “fueling right-wing extremism.” The result is bitter irony: by denying reality, governments eroded public trust and helped create the very extremism they claimed to prevent.

In the United States, the slogan “Islam is peace” was quickly absorbed by the idiom of American identity politics. Academia and media framed suspicion toward Islam as a new form of prejudice and to criticize Islamist ideas was to risk social excommunication. Within a few years, government agencies, universities and corporations started adopting “anti-Islamophobia” campaigns that blurred the line between scrutiny of belief and hostility toward believers. The same moral inversion that had reshaped Europe soon took hold in America: a militant faith was rebranded as a religion of peace and its criticism recast as an act of hate.

From the 2010s onward, progressive movements turned the “religion of peace” into a moral cause of their own. Feminists who once fought religious patriarchy now march beside men who preach it, convinced that solidarity matters more than consistency. LGBTQ activists, people who would be executed under Islamic law, carry signs reading “Queers for Palestine,” presenting radical Islam as a victim of Western freedom. In this strange alliance, identity outweighs principle and emotion replaces coherence. The same reflex that once sought moral safety now demands moral surrender.

The consequences are profound. By redefining tolerance as silence and respect as submission, progressives have created an atmosphere in which liberal values can no longer defend themselves. Criticism of illiberal practices such as forced veiling, child marriage, honor killings, female genital mutilation and the murder of homosexuals is dismissed as “Islamophobia.” Meanwhile, those who suffer most under Islamic rule — women, religious minorities, dissidents and sexual minorities — are ignored because their oppression disrupts the West’s narrative of Muslim victimhood.

The media completes the circle by reframing or omitting Islamist violence. Terror attacks in Europe are described as isolated incidents or as reactions to “marginalization,” while massacres and sectarian killings in Africa, the Middle East and South Asia rarely reach Western headlines. In this moral order, intent outweighs fact and any criticism, however reasoned, is instantly relabeled as hate.

The same moral logic now extends beyond religion into activism, where virtue itself has become a license for coercion.

The Peaceful Protests of Antifa and Extinction Rebellion

Unlike antiracism, Antifa originated in twentieth-century Europe. It began in 1932 as part of the communist resistance to the rise of fascism in Germany and Italy. The term resurfaced in the 1970s among anarchist left-wing movements that opposed the capitalist order of Western Europe, using violent tactics reframed as protection against the return of fascism. With globalization, Antifa networks spread across the Atlantic and merged with anarchist and anti-globalist groups. Apart from sporadic clashes, most protests remained marginal until 2016, when the election of Donald Trump supplied a new moral enemy. Antifa rebranded its mission as the fight against populism and began targeting anyone who deviated from the approved narrative of inclusion and progress.

Extinction Rebellion emerged later, in 2018 in the United Kingdom, as a climate movement inspired by Gandhi and Martin Luther King. It initially presented itself as non-violent civil disobedience, yet its rhetoric soon turned apocalyptic: “Act now or die.” By redefining climate change as an existential war, Extinction Rebellion since then legitimizes the paralysis of public life under the banner of saving the planet.

Both movements undermine democracy and the rule of law while claiming to defend them. Violence, intimidation, vandalism and mass disruption have become accepted practices to “protect” the planet and the weak. Antifa fights fascism by imitating it; Extinction Rebellion claims to defend life by disrupting it. Their logic rests on the conviction that their own actions stem from moral purity while dissent can only arise from evil intent. In this inverted language, as long as the cause is declared just, breaking the law is called courage and silencing others justice.

The West is no longer divided by class or creed but by design. Its fracture is sustained by a professional, urban and predominantly female class that operates the institutions of culture, education and communication. From positions insulated from material consequence, they shape the moral language that governs those who are not. In the next part, we will trace how this inversion of language embeds itself within institutions and begins to hollow out society from within.

The future you fear is already here. Recognize the script before it writes you out.

Thank you, Jeanette, for telling me why I haven't been able to abide the "news" since 1978. Fortunately that was the year I married a woman that had a practical and spiritual (Scripture inspired) handle on reality.

Your readers may find the late Friedrich Hayek's piece on THE INTELLECTUALS AND SOCIALISM (published by the University of Chicago Law Review 16, no. 3, 1949: 417-433 and republished 2025 in HAYEK FOR THE 21ST CENTURY pp 13 - 37 by The Mises Institute mises.org/) on who usually achieves cultural consensus (by weaponizing the language) and how.

Those of us who try to maintain critical thinking, he observed, eventually, are prone to allow the intellectual class, who collectively are merely dilettantes, (and, therefore, wholly incompetent to do so,) to be the arbiters of what is real and true.